Famed for its huge tabletop mountains called tepuis, the Gran Sabana (Great Savanna), on the Venezuelan-Brazilian border, tempted Shane Houbart with its endless spectacular climbing possibilities. Houbart’s plan was to create a new route on an unclimbed face on the southern side of the Upuigma Tepui. But the former British Marine got more than he bargained for.

“Don’t talk to anyone. Don’t let anyone know you’re foreign and try not to be seen by anyone. Bad people live here.”

These are the first things I hear from Alfredo Zubillaga as I wake up in Caracas, Venezuela.

After I wipe the sleep from my eyes I realise that Cory Nauman (USA) and I are alone. We’re locked in a house covered with burglar bars and there is a heavy-duty lock and chain keeping anyone from getting in. Cory turns to me and says, “So this is what it’s like to be in the most dangerous city in the world.”

Caracas has one of the highest recorded murder rates in the world. The city is set within a U-shaped valley surrounded by jungle-covered mountains. The ghettos and slums encircle the gigantic skyscrapers of Venezuela’s capital.

We spend three days cooped up for our own protection. We pass time by checking equipment, its various uses and deciding what we can ditch to lighten the load. Our plan is to create a new route on an unclimbed face on the southern side of the Upuigma Tepui. It lies in the Canaima National Park which borders Brazil and Guiana. Only teams led by the late Kurt Albert and John Arran have climbed her steep overhanging cliffs.

Lugging two crates of beer and all our equipment, we enjoy a 10-hour ‘party ride’ to the city of Ciudad Bolivar. Once there, we will charter a Cessna aircraft to transport us into the heart of la Gran Sabana. Excitement is high. Beer is flowing, music is pumping and we banter back and forth about the arduous adventure ahead.

In the morning we jump into our tiny six-person aircraft and begin the journey south to a land literally lost in time. We watch enthralled as the landscape changes from smog-filled city to vast grass plateaus and pristine jungles with flowing river systems. The occasional plantation and indigenous village come into sight and we are struck by what a truly magical and magnificent place this is.

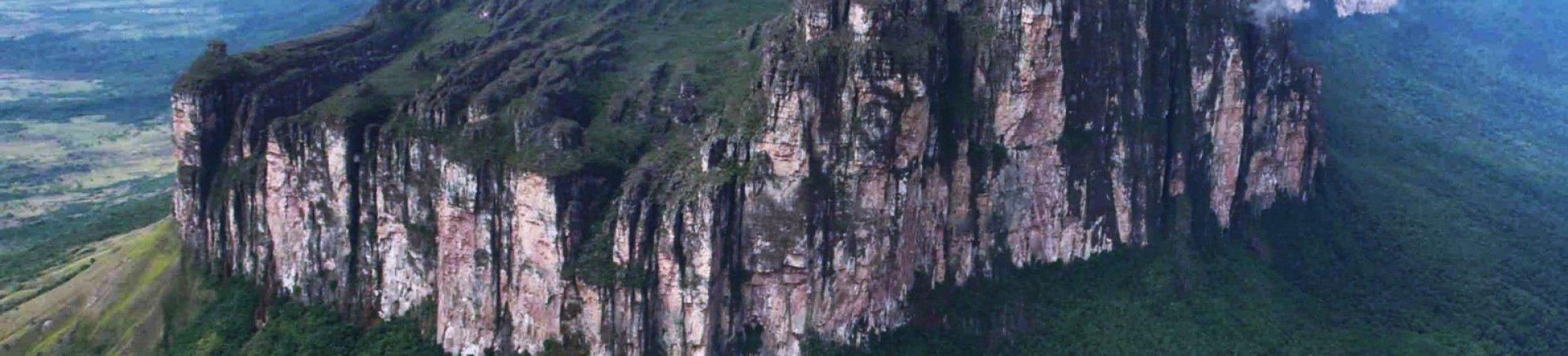

Ancient mountains

As we soar through a massive cloud, a tepui comes into view. Almost in unison, we shout out in awe! Waterfalls cascade down the sheer walls and feed the jungles below. Tepuis are an astounding two billion years old and were once connected to the supercontinent of Pangaea.

“The views are tremendously rewarding and we arrive happily at our jungle campsite after 25km where we’re greeted by a swarm of blood-thirsty sand flies named ‘pori pori’ by the Pemon.”

We fly for 1.5 hours and land in the indigenous Pemon village of Yunek. We are mesmerised by the towering band of compact sandstone cliffs which make up the impressive Akcopan Tepui. There’s enough rock to keep a population of climbers satisfied for a lifetime. If it weren’t for the complicated logistics of finding food and water, this might be a sought-after climbing destination.

The entire village runs to greet us. Curious children look at us with huge staring eyes as they hide behind parents. The villagers of Yunek are shy but warm and welcoming. Alfredo meets with the village chief, Leonardo, and enquires about hiring two porters for the two-day hike to a base camp below the wall. A price of US$25 per porter per day is agreed upon and we venture off to explore the jungle before the daily storms move in.

Loaded with 25-30kg each, we set off early. We negotiate two river systems using dugout canoes. The first day’s hike is surprisingly flat and we make quick progress under the knee-buckling weight of our equipment. The views are tremendously rewarding and we arrive happily at our jungle campsite after 25km where we’re greeted by a swarm of blood-thirsty sand flies named ‘pori pori’ by the Pemon. Luckily for everyone else, Cory receives the brunt of the thirsty swarm.

10 Camping Hacks that will Change Your Life

The next morning, we are awoken by an orchestra of different sounds and colours, and pack up for the approach to base camp, 2km from the wall. The approach is deceptive; while it looks close, it is around 16km away and has an estimated talus of 3,500 vertical feet.

This leg of the journey is steep and extremely difficult, passing through slick vertical grasslands and jungle. We are all bombarded by ‘pori pori’ until the Tepui unleashes its daily deluge of water. We are extremely thankful for the rain as it allows a much-needed respite from the sand flies. Our gratitude, however, is short lived as our packs get heavier and the ground gets more waterlogged.

Hardy locals

Our local porters, Ricardo and Ammelio (with a height of no more than five feet) show no sign of any discomfort whilst carrying their heavy traditional weaved baskets. They are hardy men and we develop a deep respect for their ability to endure the tough terrain as if it were a walk in the park. We eventually settle down on a semi-flat boulder which can accommodate a three-man tent.

“It is strangely satisfying knowing that no other human being has been on this section of this exotic mountain.”

Over the following days we hike loads to the base of Albert’s route, El Nido del Tirik Tirik (14 pitches, graded F7b) which Alfredo completed a year earlier. From our advance base camp we venture into territory where no other human being may have been before. We use machetes to cut a trail through virgin jungle to survey which wall and line we are going to tackle. In the end, we decide on the largest wall with the most obvious line and a large white streak running down most of the face.

It is strangely satisfying knowing that no other human being has been on this section of this exotic mountain. We spend two days route finding and trail cutting until the comforting jungle sounds are shattered with Cory’s screams.

Cory has been bitten by a mysterious animal and I race to get the first aid kit. He has two distinctive puncture wounds on his ankle and we assume that he has been bitten by a snake. This is extremely worrying as a high percentage of snakes in the Venezuelan jungle are highly venomous and we have no idea which one has bitten him.

Reality bites

Only now does it hit home how remote we truly are. We are at least a seven-day hike from the nearest hospital and the possibility of one of our team members dying in the next few hours is becoming a reality. I have read accounts of people being bitten here and dying four hours later.

As we are so isolated, our only option is to wait, monitoring Cory’s condition to see how he will react to the venom. We have no choice but to assess his condition through the night and then facilitate a rescue to the nearest hospital in the morning.

“With our friend in a complete state, Alfredo and I have no choice but to take the piss out of him for being soft and bleeding so much.”

Day breaks and to our relief Cory is still alive. His foot, however, is twice its normal size and charcoal black in colour. We initiate a rescue and leave our big wall gear and most of our equipment, taking only the essentials to speed the process.

Cory can thankfully hobble using his walking poles but, as we retrace our steps through the steep terrain, the poison begins to thin his blood and blood starts seeping through every available orifice, including the bite holes from the hungry sand flies. With our friend in a complete state, Alfredo and I have no choice but to take the piss out of him for being soft and bleeding so much.

We arrive at the jungle camp late at night and try making Cory comfortable. The next morning dawns and we are shocked to see that both of Cory’s feet are now in the same condition. This is a result of infection spreading and the fact that he has been over-compensating on his healthy foot. Fortunately, the terrain is flat and we arrive back to Yunek late in the afternoon.

The villagers gather to see us. One look at Cory and the village elder is summoned. She begins to cry and tells him that they will pray for him. I can’t stop myself from laughing out loud at her bluntness. Alfredo immediately stops me so that I won’t offend them! Having lost many to venomous snakes and creatures in the jungle, the Indigenous people understand the severity of the snakebite, and mourning and praying follows.

Leonardo, the chief, has a radio and tries to establish contact with a radio station in Santa Elena. Miraculously, a Cessna plane passing over a neighbouring valley hears the distress call and immediately comes to us. Amazingly within three hours of arriving in Yunek we land in Santa Elena on the Brazilian border. An ambulance is waiting for us and Cory is rushed to the local hospital.

Five-star treatment

The hospital staff are fantastic and give the American gringo five-star treatment with the meagre supplies they have. But after three days Cory has had enough of the poor sanitation and is ready to leave. The hospital, however, refuses to release him and he is watched closely by hospital security.

That evening, after a few beers, Alfredo and I decide to conduct our first-ever hospital breakout. We survey the security guards’ movements. To get Cory out, we have to bypass two security gates and three guards. A disguise is organised for Cory: fresh clothes, sunglasses and a large hat. We then give him strict instructions to stay 20m behind me while I deal with the guards and create diversions. I tell him to walk like he owns the place and don’t stop for anything.

Alfredo has a taxi waiting and as we casually walk towards it the doctors notice that Cory is outside and begin to follow us. We make a run for it and I stupidly yell at Cory to pull the drip out of his arm. Blood sprays everywhere. We dive into the taxi and speed off while trying to stop the bleeding from his arm. Finally, under control, all we have to do is watch out for the corrupt army and police who have certainly been informed of Cory’s sudden disappearance.

The operation is conducted with a level of precision a military general would be proud of. We lie low while waiting for the heat to die down and then arrange the funds necessary to get Cory to an American hospital and to get Alfredo and myself back to the jungle to continue with our climb.

After celebrating our accomplished mission, we depart for the jungle, one member down. Alfredo and I retrace our steps back to our advanced base camp and finish cutting our path to the wall. We are on a tight timescale now. At over 400m high, this is the largest overhanging wall I have ever laid eyes on.

“The sense of being alive overwhelms me as we climb up the overhanging puzzle.”

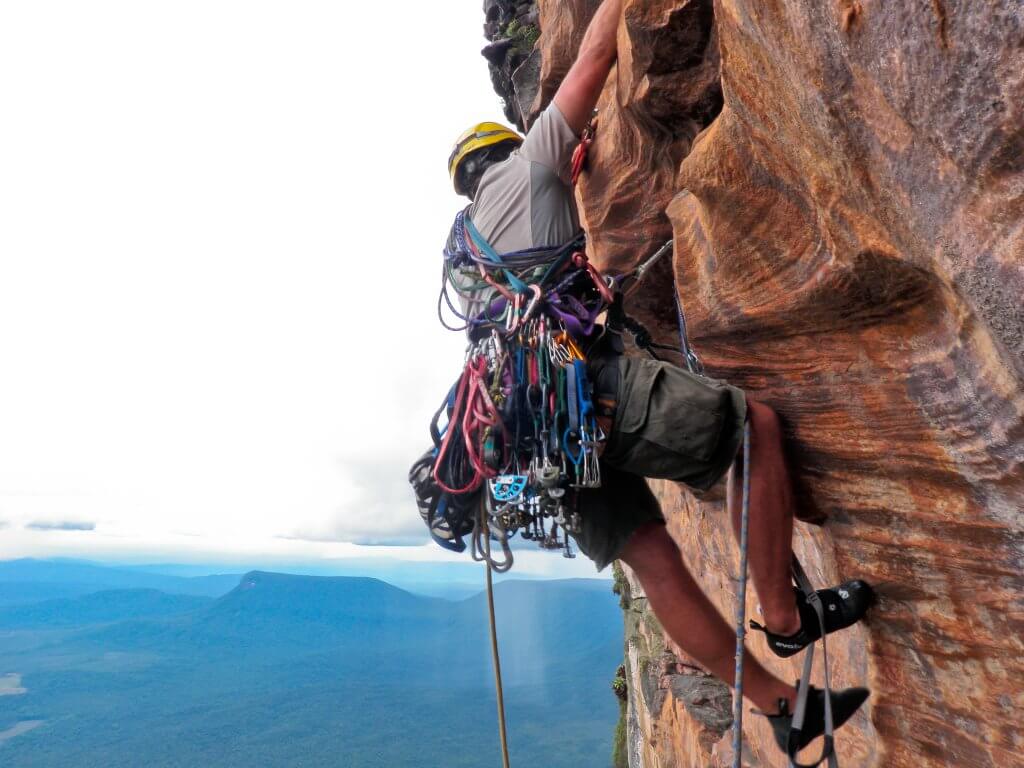

After two more days of hiking loads we finally get started. We are weighed down with 8l of water, 20kg of food, equipment and more climbing gear than I can ever imagine carrying. The first haul isn’t as bad as we think it might be, taking into account that we have a combined weight of over 150kg in two haul bags and a portaledge, not to mention the fact that we are hauling up a largely overgrown slab.

Climbing at last

We ease ourselves into the complexities of route finding during the first three pitches. After the third pitch, the true overhanging characteristic of the rock becomes apparent and it is glorious. The fourth pitch is a beautiful lay back pitch with a small technical roof of dirty hand jams.

The climbing is adventurous. I’m tried and tested to my limits as this is my first new route and it’s in the middle of the South American jungle. The sense of being alive overwhelms me as we climb up the overhanging puzzle. Aesthetic climbing pushes my senses with big moves and good holds. Some of the run-out sections grip me to the core as I concentrate on my breathing and not gripping the rock too tightly.

The climbing gets better and more solid with every upward inch we gain. Cracks system link up with horizontal breaks, providing well-protected climbing with occasional sections of no protection for up to 25 feet. Never before have I ‘heel hooked’ so much on an entire climb to conserve energy and save my forearms from the ‘pump’.

The grades stay within the 5.10 range with a few 5.11 pitches which Alfredo and I largely on-sight. The rock is generally solid with a few loose sections here and there. I start to gather a real appreciation for the pioneers of the late 1960s when they began navigating the big walls of Yosemite in the USA.

The climbing is more mentally and physically draining than anything I have experienced in my life. Alfredo handles the pressure like a world heavy weight climbing champion. I have never seen someone grin so effortlessly whilst ‘cruxing out’ on a run out 5.12+ pitch which is by far the most beautiful of all the pitches.

For the first three nights we sleep on the portaledge, finding small spaces to cook on as we watch the setting sun and appreciate the views and stunning bird life. It rains every day and we don’t get touched by a single drop as the large overhang protects us.

There is never a dull moment. We watch weather systems move in and out, with the heavy clouds releasing their water above the jungle. Humming birds fly around us, curious never having seen a human being before. Swallows play and fly parallel with the walls, narrowly pulling away from impact at the very last second. Wild colourful jungle parrots swarm around us full of vibrant sounds and chatter.

Over the next four nights we camp in blowhole caves and sleep on the most amazing ledge I have ever had the pleasure of bivvying on. Storms roll past and the mountain thunders around us while we climb through dense cloud, making route finding even more challenging.

“I make a dynamic lunge to a hold that I haven’t tested, hear a loud snap and see the hold fly into my helmet with a loud thud. Almost immediately my foot peels off and I see the wall rush in front of my face.”

Most of the climbing is free with the exception of pitch 11 and 12. Pitch 11, being a tenuous A2+ pitch with two tension traverses followed by pitch 12 which is C2+ with mandatory technical free climbing of 5.11-.Whilst hauling on the 11th pitch, Alfredo’s sling and rope protector get cut straight through! Luckily he has backed everything up correctly and doesn’t end up losing the haul bag or, more importantly, his life. I can only laugh at him while I finish cleaning the pitch – Alfredo has a blasé look on his face. Once the weight of the haul bag is off him we both giggle at how lucky he is.

Then, while jugging on our fixed lines of the final pitches, my rope is nearly dealt the same fate thanks to a sharp protruding rock. We both make a mental note to remember extra rope protectors next time!

On the eighth day, we climb through interesting grooves with ancient rock formations. On pitch 13 I take my first and only fall on the route because I become complacent with the solidity of the rock. I make a dynamic lunge to a hold that I haven’t tested, hear a loud snap and see the hold fly into my helmet with a loud thud. Almost immediately my foot peels off and I see the wall rush in front of my face. Everything slows down while I’m in mid-air and I realise that I have only one piece of protection in just above the belay. I fall 30 feet, passing Alfredo and narrowly missing the ledge that he is belaying on!

Topping out

After my heart rate eases I recompose myself and finish the pitch, this time testing every hold as I progress upwards. We pass the last overhang and hit thick jungle with no more eventful climbing. We decide not to ‘bush wack’ to the summit as it’s hard to gauge how much further it is to the top. The vegetation looks thick and our rations are running low. Food supplies, clothes, gear and, strangely enough, even our mobile SIM cards were stolen by the local people the night before we left, while we were asleep.

Perched on our ledge we celebrate our grade V 5.12+ A2+ (14 pitches, 520m) route with a bottle of rum and we name it ‘The Hospital Breakout’. The next morning, we rappel down, reversing the route. Only two of the rappels are difficult as a result of the overhangs but overall we have few complications. Only seven-hand drilled bolts are placed to protect run out sections of climbing and to facilitate rappels.

Storms are still in full force and once we hit the ground we no longer have the protection of the overhangs. We get drenched. In eight years of military service in the British Royal Marines I have never experienced such horrific rain. We decide that to save time we will take everything back to our advanced base camp in one load, which weighs well over 30kg each.

It takes us 1.5 hours to cover 1km in the downpour. The steep terrain becomes treacherously slippery and loose. The ground gives way and I slip eight meters down a steep slope, my momentum (and further injury) luckily being stopped by a tree.

Our progress is stopped when the seemingly timid stream where we filled our water bottles has changed into a raging waterfall 50m wide. We spend a night completely soaked and close to hypothermia. The next morning we wake to blue skies and find that if we had camped 30m to our left we would have spent the night dry! Next time I will look a little bit harder before giving up and settling down for the night.

We eventually decide that we are too rundown and have far too much equipment to carry. Out of respect to the mountain we are reluctant to leave equipment or burn any rubbish so we organise the gear into four manageable loads and take two with us. It is a very strenuous day as we make the 36km trek back to Yunek in a single push.

We arrive feeling equal amounts of fatigue and elation. A team of porters is assembled to gather our remaining gear the following day. To pass time, Alfredo and I hire a dugout canoe and chill out on the river. We go for a jaunt in the white rapids and have great fun.

Homeward bound

We charter a Cessna aircraft back to Santa Elena and, when we arrive, I realise my passport is missing after packing it in my bag the day before. We contact the villagers by radio and Leonardo informs us that it isn’t there. We believe that because we refused to pay a passing fee to a neighbouring village’s chief, they stole my passport while we were on the river.

I spend the next seven days agonising over how I’ll get home. Luckily a group of 30 cute Danish girls is passing through town and they take my mind off of my situation. I then have to deal with crooked lazy cops who have no interest in helping me, but I persist. I eventually arrive in Caracas and the British Embassy is more than willing to help. I obtain an emergency passport that same day.

Adding to the excitement, while trying to obtain a travel visa for my emergency passport, I nearly get shot at the American embassy. I’m so desperate to make my flight the following morning that when I am stuck in traffic, I decide to sprint to get to the embassy so that I make my appointment. As expected, the American embassy get very touchy when they saw a frantic young man with a dark complexion and a large unkempt beard hurtling towards them at full speed. I find myself surrounded by 10 masked men pointing their assault rifles at me. I am promptly thrown to the floor, knees thrust into my neck and handcuffed.

I can’t deny that I’m impressed by their speed and efficiency. I am taken into a room and appropriately interrogated. Luckily the US marine sergeant sympathises with my story and gives me a firm telling off. I apologise profusely and receive my Washington-approved travel visa with two minutes to spare.

This, however, is not the end of my problems as I get held in the US due to a numbering error on my passport and visa which don’t match the system’s. Added to that, two of my flights are delayed and the airline loses my bags – brilliant! For all the anguish that we went through, it is still the most epic adventure I’ve ever had. The name of the route clearly defines the whole adventure. Against all the odds and the challenges we faced we still ‘sent’ (Yosemite slang for ascent) and put up a new route. To this day we still don’t know what bit Cory. He is alive and climbing after receiving medical attention in Miami.

Check out our Hard as Nails podcast:

Feeling inspired to have your own adventure? Check out the links below to get you started:

- Hiking: A Beginner’s Guide to Exploring the Mountains

- 6 of the Best Mountain Walks in Ireland

- Hiking Boots: 6 of the Best