The Paragliding World Cup 2015 is just about to start in a far-flung corner of the globe – Bir, India. So what better time for Barry Roberts of Wilderness Medical Training to tell you about his extraordinary Indian paragliding adventure when he visits this tiny village in the Joginder Nagar Valley withing the Dhauladhar Range of the foothills of the Indian Himalayas.

Dangling, wrapped around two electricity cables, a large fruit bat hung lifeless. Was this an omen of what Bir had in store?

What is paragliding?

Paragliding (called parapenting in France) is unpowered free flight. The pilot hangs in a harness suspended from the glider above which is an elliptically shaped wing that gets its rigidity from air pressure in its cells. There is no engine (that’s paramotoring) and we take off by running down steep slopes into the wind, not by jumping off cliffs (that’s base jumping). We carry an emergency reserve parachute.

Paragliders are deemed an aircraft and are subject to a country’s air laws (restricted airspace around airports for example) and the forces of nature, especially wind and sinking and lifting parcels of air, called thermals. We can’t fly if it’s too windy because it gets turbulent (which increases by the square of the wind speed). Solar radiation powers thermal updrafts of air to keep us afloat. The sun is our engine and ultimately determines how long we can stay in the air and therefore how far we can fly. Portability is the great attraction of this aircraft with a full rig weighing in at 10-15kg.

Bir: The paragliding capital of India

As the sun shut down last autumn, and in the lull between the waning flying season and upcoming ski season, I recruited chums Chris and Paul to join me on a November paragliding mission to Bir, India.

The village of Bir (pronounced beer) is in the mountainous northern Indian state of Himachal Pradesh – HP for short. It is a very small village with a very big paragliding reputation. ‘Billing’, the name of the launch point at 2,428m, Himalayan griffin vultures (HGVs) and forbidding tales of ‘going over the back’ into the higher mountains are all part of Bir flying folklore.

Bir features on a relatively short list of epic autumn destinations for northern hemisphere pilots; Manilla (Australia), South Africa, Nepal and Brazil are some other alternatives. I last visited India in 1985 after months of Himalayan trekking and climbing in Nepal. Ravaged by illness, 10kg lighter and out of cash, I ran the gauntlet of New Delhi airport to get home (then in Canada). Three decades on, I initially dismissed India as an autumn flying destination; too chaotic with difficult and protracted travel I remembered. But I dug deeper into researching Bir and was hugely inspired by the paragliding travel book Classic Routes and the photographs and description of Bir’s 90km+ ‘out and return’ ridge run to Dharamshala, home of the Dalai Lama.

Landing out is fraught with dangers; power lines and cables indiscriminately criss-cross the land and nowhere is really flat.

‘Out and return’ means just that; take off, fly away and fly back to where you started. If you landing ‘out’, it’s an adventure in itself getting back to base. Last summer in the UK I flew 127km, landing near Hull five hours later. It took much longer to get home and included hitchhiking, a train ride and finally a taxi to my car.

In nine days of flying in Bir, I landed out once. Landing out is fraught with dangers; power lines and cables indiscriminately criss-cross the land and nowhere is really flat. Large fields are rare. Terraced fields are more the norm with the land subdivided by earthen walls in a patchwork, stepped pattern. High in the air, it’s a beautiful sight. Down low, it’s nerve-racking. Once low, paragliders can’t fly back up so landing is inevitable.

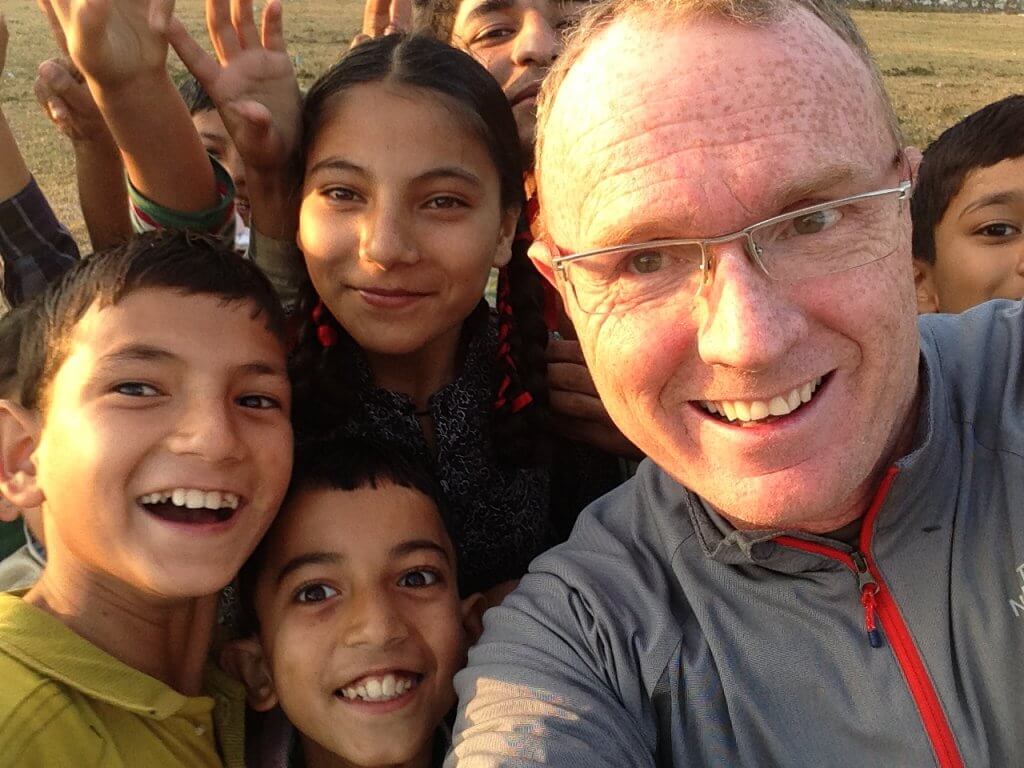

This is how you connect with the locals. Drop out of the sky and take selfies with them.

Only one major road runs through the Kangra valley so the wise (and lazy) pilot lands as close to the road as possible to avoid a long hike to it. My out landing was in a sports field that didn’t seem well used, maybe because it had a huge rock in the middle of it! Before my feet touched down, a dozen or more kids raced to the scene together with adults who dropped their farm tools and came over to meet me. This is how you connect with the locals. Drop out of the sky and take selfies with them. A taxi driver spotted me coming into land and was waiting to whisk me back to Bir, an hour’s journey away, but not before visiting his house to meet his extended family, read with his 12-year-old son (who aspires to be an engineer) and having a refreshing cup of tea.

Flying is thirsty work despite carrying a water bladder. I’m a recent convert to using an in-flight pee tube, the unsavoury details of which my wife forbids me to publish. Suffice to say I can relieve myself in the sky. It’s not pretty but it works.

On our first attempt to fly to Dharamshala, we managed about 20km before a very large cloud enveloped the mountain. I got sucked up into it for a minute and hastily flew out to the sunny (southern) side of the cloud. Then I turned tail for Bir. Flying in clouds can be lethal. It is cold, wet and totally disorienting. A 40km out and return flight in the UK would be a minor triumph. In Bir, this was a short hop.

Vultures and eagles became my friends and it felt like they were trying to be helpful, to lead me to the best climbs.

A few days later we attempted the route to Dharamshala again and were a little wiser about the challenge ahead. A group of pilots flying together is called a ‘gaggle’. It feels safer to fly in a gaggle and you can follow who has found the lift if you haven’t. We fly with radios but they never seem to work. It’s easier to shout across a thermal to each other as we circle and spiral skywards.

I found myself flying alone a lot throughout the trip but there were always birds marking the thermals and circling upwards to cloud base. Vultures and eagles became my friends and it felt like they were trying to be helpful, to lead me to the best climbs. They can be sleepy and more than once I shouted at a bird that seemed oblivious of me and might fly into my lines. (A Russian pilot crashed but survived several years ago when his lines got entangled with a young eagle). I can’t think of any other wild animal that apparently cooperates or plays with humans with the exception perhaps of dolphins. This connectedness with nature and natural forces – creatures in the sky and the invisible thermals we need to stay aloft – are two aspects that make paragliding incredibly unique and special.

En route to Dharamshala, there are several major forested, rocky spines that peel off the main east-west oriented ridge. These spines are thermal trigger so we fly from spine to spine getting lift and height, then glide directly across the gap to the next spine. The lift can be very close to the spine so it’s demanding low flying and it’s easy to be distracted by troops of monkeys in the trees below. That’s how low you can get.

After three hours I caught up with two pilots who planned to land in Dharamshala below. Not me. It was time to U-turn and fly back to Bir. By now the light valley wind had switched from an easterly to a westerly to push me home. Full speed is 70 kmph with a tail wind but it’s necessary to stop and climb in the thermals and this takes time, especially later in the day as the thermals weaken. It’s only 45km back. How long can it take?

A good pilot knows when and how to shift gears. Sometimes you speed up and other times you waft around milking the light lift. In addition to the pilot’s skill, attitude and stamina, a vario is a vital instrument to successful flying. This super fast GPS instrument measures how fast you climb and even shows where the last thermal was so you can fly back into it. It’s tempting to not climb high enough and prematurely glide to the next ridge but the risk is arriving too low to connect with any lift. My mental mantra was, “Don’t rush, find the lift, work it, be patient and you’ll get back.” And I did.

I’m often asked if paragliding is dangerous. It can be. Chris witnessed a pilot floating down on his reserve parachute (apparently a daily event). We heard about a Kiwi pilot in hospital with a shattered pelvis and watched a Russian pilot with a broken leg get painfully scooped off the landing field into a makeshift ambulance. He stalled his glider and fell 10m out of the sky. I met a French pilot in a lower leg cast. A British acquaintance landed in the trees. Our trip was incident free – not even a case of Delhi belly – and our trio clocked up 60 hours total flying time.

The combination of beautiful wildlife, sporting flying, welcoming natives, trusted companions and a nightly curry buffet washed down with chilled Kingfisher lager made Bir the best flying trip any of us have ever done. Any place named beer must be good. And it certainly was.

The low-down: What you need to know

Bir is about 500 miles north of Dehli. If you’re not an experienced pilot and would like to try a tandem ride, there are tonnes of local companies that can help. They cost about 3000 rupees (€40 approx) for a flight which is cheap. And there are lots of cheap hotels too but you should book ahead.

Barry Roberts has been a paraglider pilot for 15 years. He’s flown off Mont Blanc and the highest peak in the Arctic in winter. As an expedition guide, he’s been on 25 major expeditions and has reached the summit of Everest. He’s the commercial director of Wilderness Medical Training and he lives between the Lake District, England and Chamonix.

Check out our Hard as Nails podcast:

Other articles you might be interested in: